Transcontinental Railroad:Classroom Resources

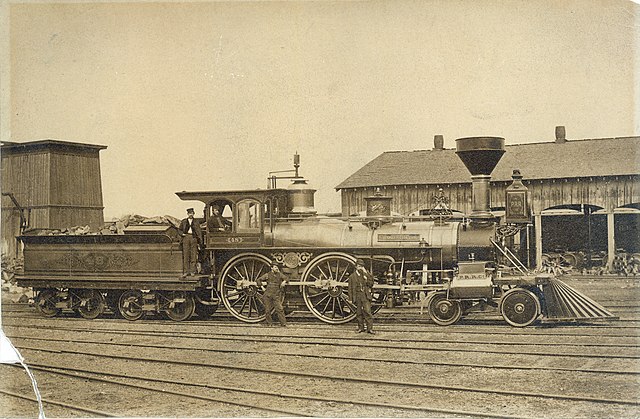

On May 10, 1869, two locomotives faced each other at Promontory Summit, Utah. A crowd gathered as Leland Stanford raised a silver hammer to drive a ceremonial Golden Spike into the final rail tie. He swung—and missed. The crowd laughed, someone else finished the job, and a telegraph operator tapped out a single word that echoed across the nation: “Done.”

After six years of backbreaking labor, engineering marvels, and human sacrifice, the Transcontinental Railroad was complete. America was finally connected from coast to coast, and nothing would ever be the same.

For teachers, this event offers rich opportunities to explore themes of innovation, immigration, expansion, and consequence. This comprehensive guide provides everything you need to bring this transformative era to life in your classroom.

Transcontinental Railroad Facts: What Students Need to Know

The Vision and Planning

Long before construction began, a young engineer named Theodore Judah dreamed of a railroad spanning the continent. While others dismissed the idea as impossible, Judah spent years surveying routes through the treacherous Sierra Nevada mountains, proving it could be done.

The debate over where to build the railroad had stalled in Congress for years. Northern states wanted a northern route; southern states demanded a southern path. When the Civil War began and southern states seceded, the decision became simple. President Abraham Lincoln signed the Pacific Railroad Act in 1862, authorizing construction along a central route and providing massive government support.

The timing was no accident. Lincoln understood that a transcontinental railroad would bind California and its gold wealth firmly to the Union, move troops and supplies efficiently, and fulfill the nation’s belief in Manifest Destiny.

The Two Railroad Companies

Two companies would build the railroad from opposite directions until they met. The Central Pacific Railroad started in Sacramento, California, and built eastward. Led by the “Big Four”—Leland Stanford, Collis Huntington, Mark Hopkins, and Charles Crocker—this company faced the immediate challenge of crossing the Sierra Nevada.

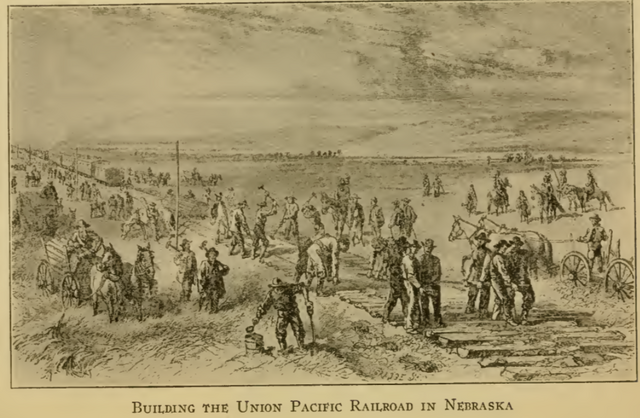

The Union Pacific Railroad began in Omaha, Nebraska, and built westward across the Great Plains. Vice President Thomas Durant and chief engineer Grenville Dodge led this effort, facing different but equally daunting challenges: vast distances, harsh weather, and conflicts with Native American tribes.

The government incentivized speed by paying each company per mile of track laid—$16,000 per mile on flat land, $48,000 per mile in the mountains. This turned construction into a race, with both companies pushing workers to lay track at unprecedented speeds.

Key Locations on the Transcontinental Railroad Map

Understanding the geography helps students appreciate the enormous challenge. Sacramento, California served as the Central Pacific’s starting point and supply hub. Omaha, Nebraska launched the Union Pacific’s westward push. The Sierra Nevada Mountains presented the most formidable obstacle—granite peaks, steep canyons, and brutal winters. Promontory Summit, Utah became the historic meeting point, now preserved as Golden Spike National Historical Park.

The completed railroad stretched nearly 1,800 miles, crossing prairies, deserts, and mountain ranges that had taken pioneers six months to traverse by wagon.

3c Transcontinental Railroad 75th Anniversary single, 1944, U.S. Post Office — U.S. Bureau of Engraving and Printing, Wikimedia Common

When Was the Transcontinental Railroad Completed?

The Golden Spike Ceremony on May 10, 1869 marked the official completion. Dignitaries gathered at Promontory Summit as the final rails were laid. Two locomotives—Central Pacific’s “Jupiter” and Union Pacific’s “No. 119″—pulled forward until they nearly touched.

Celebration of completion of the First Transcontinental Railroad at what is now Golden Spike National Historic Site, Promontory Summit, Utah.

Leland Stanford was handed a silver hammer to drive the ceremonial Golden Spike. In a moment of irony that delighted the crowd, he swung and completely missed the spike. Someone else quietly finished the job. Telegraph wires connected to the spike and hammer sent an electrical signal across the nation, triggering celebrations in cities from coast to coast. Bells rang, cannons fired, and parades filled the streets.

Six years of construction had finally ended. The nation was connected.

Building the Railroad: Workers and Challenges

The Workforce

The Transcontinental Railroad was built by immigrant labor, and understanding who built it is essential to understanding the full story.

The Central Pacific initially hired Irish immigrants, but struggled to find enough workers willing to endure the dangerous mountain construction. Charles Crocker made a controversial decision: hire Chinese immigrants. Despite skepticism about whether Chinese workers could handle the brutal labor, they quickly proved themselves invaluable.

At its peak, the Central Pacific employed over 12,000 Chinese workers—roughly 90% of their workforce. These men, many of whom had come to California during the Gold Rush, performed the most dangerous work: drilling tunnels through granite, handling unstable explosives, and dangling from cliffs in wicker baskets to plant charges. They earned less than white workers and faced widespread discrimination, yet their contributions made the railroad possible.

The Union Pacific relied heavily on Irish immigrants, many fleeing the Great Famine, along with Civil War veterans from both the Union and Confederate armies. These workers faced their own dangers crossing the open plains, including extreme weather and conflicts with Native American tribes defending their territories.

Construction Challenges

Both companies faced extraordinary obstacles. The Central Pacific’s Sierra Nevada crossing required tunneling through solid granite. The Summit Tunnel alone stretched 1,659 feet and took 15 months to complete. Workers chipped away at the rock by hand, advancing just eight inches per day. When nitroglycerin was introduced to speed the work, accidental explosions killed hundreds.

Winters brought avalanches that buried entire work camps. During the brutal winter of 1866-67, workers lived in tunnels beneath 40 feet of snow, working around the clock in shifts. The exact death toll remains unknown, but estimates suggest over 1,000 Chinese workers died during construction.

The Union Pacific faced different challenges. The Great Plains seemed easier to cross, but workers battled extreme heat, scarce water, and violent conflicts. Native American tribes, recognizing that the railroad threatened their way of life, attacked work crews and supply trains. The company hired armed guards and even received military protection.

Engineering Feats

The engineering achievements still impress today. Workers carved fifteen tunnels through the Sierra Nevada, using hand drills, black powder, and later nitroglycerin. They built massive wooden trestle bridges across canyons, some standing over 100 feet high. Curved tracks hugged mountainsides where straight lines were impossible.

In the flat plains, speed became the focus. Near the end of construction, Central Pacific workers set an astounding record: 10 miles of track laid in a single twelve-hour day. This required precise coordination—teams placing ties, positioning rails, driving spikes—all moving in perfect rhythm.

Effects of the Transcontinental Railroad

Travel and Communication Revolution

Before the railroad, traveling from New York to San Francisco meant a six-month journey by wagon train or a dangerous sea voyage around South America. After completion, the same trip took just six days.

This transformation affected everything. Business people could travel between coasts for meetings. Families separated by the continent could reunite. Mail that once took months arrived in days. The telegraph lines running alongside the tracks enabled near-instant communication.

The railroad also created something we take for granted today: standard time zones. Before 1869, every city set its own local time based on the sun. This worked fine until trains needed schedules. How could you publish a timetable when every station used different clocks? The railroads eventually standardized four time zones across the country, bringing order to American timekeeping.

Economic Transformation

The railroad transformed the American economy virtually overnight. Goods that once took months to transport could cross the country in days. Eastern factories could sell products in California. Western mines could ship ore to eastern smelters. The vast agricultural potential of the plains could finally reach distant markets.

Railroad boomtowns sprang up along the route. Where trains stopped, towns grew—some thriving, others fading when the railroad moved on. Cities like Cheyenne, Wyoming and Reno, Nevada owe their existence to the railroad.

The cattle industry exploded. Ranchers could now drive cattle to railroad towns, load them onto trains, and ship them to meatpacking centers in Chicago. The era of the great cattle drives and the cowboy legend began.

Westward Expansion Accelerated

The railroad fulfilled the vision of Manifest Destiny by making western migration practical for ordinary families. The Homestead Act of 1862 offered free land to settlers willing to farm it. With the railroad, these settlers could actually reach their claims and ship their crops to market.

Populations shifted dramatically. New states entered the Union as territories filled with settlers. The Great Plains, once dismissed as the “Great American Desert,” became America’s breadbasket. Within a generation, the frontier was declared officially closed.

Impact on Native Americans

The railroad brought devastating consequences for Native American tribes. The construction crews and settlers that followed disrupted ancient migration routes and hunting grounds. More destructive was what happened to the buffalo.

Millions of buffalo had roamed the plains, providing food, clothing, shelter, and spiritual meaning for tribes like the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho. Railroad companies hired hunters to kill buffalo—partly to feed workers, partly to eliminate the herds that sometimes blocked trains, and partly as deliberate policy to weaken Native resistance.

Within two decades, the buffalo population collapsed from tens of millions to near extinction. Without the buffalo, traditional Plains Indian life became impossible. Tribes faced a terrible choice: accept reservation life or starve. The railroad didn’t cause all the injustices Native Americans suffered, but it accelerated and enabled them in profound ways.

Environmental Changes

The railroad transformed the physical landscape. Forests were cleared for railroad ties—each mile of track required 2,500 ties. Mining operations expanded to extract the coal and iron needed for locomotives and rails. New towns dotted the previously empty plains.

The changes rippled outward. Farmland replaced prairie. Fences divided open range. Rivers were dammed. Within decades, the landscape pioneers had encountered was fundamentally altered.

Key People of the Transcontinental Railroad

Theodore Judah was the visionary engineer who surveyed the Sierra Nevada route and tirelessly promoted the railroad. He secured funding and political support, but died of yellow fever in 1863, never seeing his dream completed.

Leland Stanford served as Central Pacific president and California governor. He drove the ceremonial (missed) Golden Spike and later founded Stanford University using his railroad fortune.

Charles Crocker oversaw Central Pacific construction and championed hiring Chinese workers. His drive to beat the Union Pacific pushed workers to their limits.

Thomas Durant led the Union Pacific as vice president, focused more on financial schemes than construction quality. He was later implicated in the Crédit Mobilier scandal.

Grenville Dodge served as Union Pacific chief engineer, bringing military precision to railroad construction. His experience as a Civil War general proved valuable in coordinating massive work crews.

Teaching the Transcontinental Railroad: Grade-Level Approaches

Elementary (Grades 3-5)

For younger students, focus on the story and the race. Two teams starting from opposite ends of the country, building toward each other—this narrative captures their imagination. Key concepts for this age group include the basic story of two railroads meeting, map skills showing the route from east to west, worker stories and daily life on the construction crews, the Golden Spike celebration, and simple before-and-after comparisons of travel times.

Use visuals heavily at this level. Historic photographs of workers, locomotives, and the Golden Spike ceremony bring the story to life. Simple maps showing the route help students visualize the enormous distance involved.

Middle School (Grades 6-8)

For Middle schoolers introduce primary sources—photographs, newspaper accounts, letters from workers. Explore the experiences of different groups: Chinese workers facing discrimination, Irish immigrants seeking opportunity, Native Americans watching their world change.

Focus areas for this age group include primary source analysis and historical thinking, multiple perspectives on the same events, economic and political causes and effects, connections to Civil War and Reconstruction, ethical questions about progress and its costs, and the gap between celebration and reality.

Students can debate whether the railroad’s benefits justified its costs, or research specific groups’ experiences for presentations that illuminate different sides of the story.

Standards Alignment

The Transcontinental Railroad connects to multiple educational standards. Common Core ELA standards include informational text reading, writing arguments with evidence, and vocabulary in context. Social Studies standards address westward expansion, industrialization, immigration, and Native American history. Historical thinking skills include analyzing cause and effect, evaluating multiple perspectives, using primary sources, and weighing costs and benefits.

Classroom Resources and Activities

Reading Resources

Build background knowledge through varied reading materials. Look for reading passages at multiple levels for differentiation. Primary sources like newspaper accounts of the Golden Spike ceremony or letters from workers provide authentic voices from the era.

For longer texts, “Ten Mile Day” by Mary Ann Fraser offers an engaging account of the record-setting final push. “Coolies” by Yin tells the story of Chinese workers through a picture book format suitable for younger readers or as an introduction for older students.

Interactive Activities

Railroad Race Simulation: Divide the class into Central Pacific and Union Pacific teams. Give each team challenges representing construction obstacles—math problems for tunnel measurements, puzzle pieces for laying track, physical challenges for moving supplies. Award points per “mile” completed. This kinesthetic activity captures the competitive spirit of the actual construction.

Map Skills Activity: Provide blank maps and have students plot the railroad route, marking key cities, mountain ranges, and the meeting point. Calculate distances between points. Compare the railroad route to earlier pioneer trails.

Engineering Challenge: Using limited materials (popsicle sticks, cardboard, tape), challenge students to build trestle bridges that can support weight. This hands-on activity illustrates the engineering problems workers faced.

Perspective Role-Play: Assign students different personas—a Chinese worker, an Irish immigrant, a Native American watching the railroad approach, a business owner in San Francisco. Have them write diary entries or participate in a structured discussion from their character’s viewpoint.

Timeline Construction: Create a classroom timeline of key events from the Pacific Railroad Act (1862) through completion (1869) and immediate effects. Students can add events, images, and descriptions throughout the unit.

Worksheets and Printables

Effective comprehension activities include vocabulary matching with key railroad terms (transcontinental, locomotive, telegraph, summit), timeline activities sequencing major events, cause and effect graphic organizers exploring the railroad’s impacts, compare and contrast charts examining life before and after the railroad, multiple perspective analysis worksheets, reading comprehension activities with primary and secondary sources, and map skills worksheets plotting the route.

Multimedia Resources

Virtual Field Trips: Golden Spike National Historical Park offers virtual resources and ranger presentations. The California State Railroad Museum provides online exhibits and primary sources.

Videos and Documentaries: PBS’s “Transcontinental Railroad” and History Channel documentaries offer grade-appropriate content. Preview carefully for your specific audience.

Interactive Maps: Digital tools allow students to explore the route, see historic photographs at specific locations, and understand the geographic challenges.

Historic Photographs: The Library of Congress and National Archives contain thousands of images from railroad construction. Photographs of workers, equipment, and the Golden Spike ceremony make excellent primary sources.

Assessment Ideas

Discussion Questions: Why was the government willing to give so much money and land to railroad companies? Who really built the Transcontinental Railroad? What groups benefited and what groups suffered? Was the railroad worth its costs?

Writing Prompts: Write a letter home as a Chinese or Irish worker describing your experiences. Argue whether the Transcontinental Railroad should be celebrated, mourned, or both. Compare the Transcontinental Railroad to a modern infrastructure project.

Project-Based Learning: Students can research and present on specific aspects of railroad history, create museum exhibits examining different perspectives, produce podcasts telling untold stories, or design memorials honoring workers.

Sample 5-Day Unit Plan

Day 1: Vision and Planning Begin with a hook—show the famous Golden Spike photograph and ask students what they think is happening. Introduce the Pacific Railroad Act and the two competing companies. Use map activities to establish geography and discuss why the railroad mattered so much.

Day 2: Workers and Construction Focus on who actually built the railroad. Examine Chinese and Irish worker experiences through primary sources and readings. Discuss working conditions, pay disparities, and the dangerous work of tunneling and blasting.

Day 3: Engineering and the Race Explore the construction challenges and engineering solutions. The trestle bridge building activity works well here. Discuss the race between companies and the record-setting final push.

Day 4: Completion and Effects Cover the Golden Spike ceremony, then pivot to consequences. Use graphic organizers to map effects on different groups: travelers, businesses, settlers, and Native Americans.

Day 5: Assessment and Reflection Student presentations or projects, written assessment, and whole-class discussion of essential questions. End by connecting to modern infrastructure debates.

Essential Questions for Student Inquiry

Strong essential questions drive meaningful learning. Use these throughout your unit:

- Why was connecting the nation by railroad considered so important?

- Who really built the Transcontinental Railroad, and how are they remembered?

- What were the costs and benefits of completing the railroad?

- How did the railroad change life for different groups of Americans?

- Was the Transcontinental Railroad worth its human and environmental costs?

- Whose stories get told when we remember the railroad, and whose are forgotten?

- How do we weigh progress against the harm it can cause?

These questions have no simple answers, which makes them perfect for developing critical thinking skills and genuine historical inquiry.

Bringing It All Together

The Transcontinental Railroad offers a powerful case study in American history—a story of vision and ambition, innovation and exploitation, triumph and tragedy. Teaching it well means going beyond the Golden Spike celebration to explore the full human story: the thousands of workers who built the railroad, the Native Americans whose lives it disrupted, and the nation it transformed.

The railroad brought genuine benefits—faster travel, economic growth, national unity—but those benefits came with real costs paid by real people. Understanding this complexity prepares students to think critically about the world they’re inheriting.

Download Teaching Resources

Ready to build a great unit on the Transcontinental Railroad? Explore our collection of teaching resources:

- Reading Passages: Grade-leveled informational texts covering all aspects of railroad history. Ready-to-use activities with answer keys

- Vocabulary Resources: Fashcards, matching activities, and context clues exercises

- Assessment Materials: Quizzes aligned to standards

Visit Workybooks to access our complete Transcontinental Railroad teaching collection and hundreds of other standards-aligned resources for K-8 educators.

Looking for more history teaching resources? Subscribe to our platform for free resources, and the latest additions to our educational library.